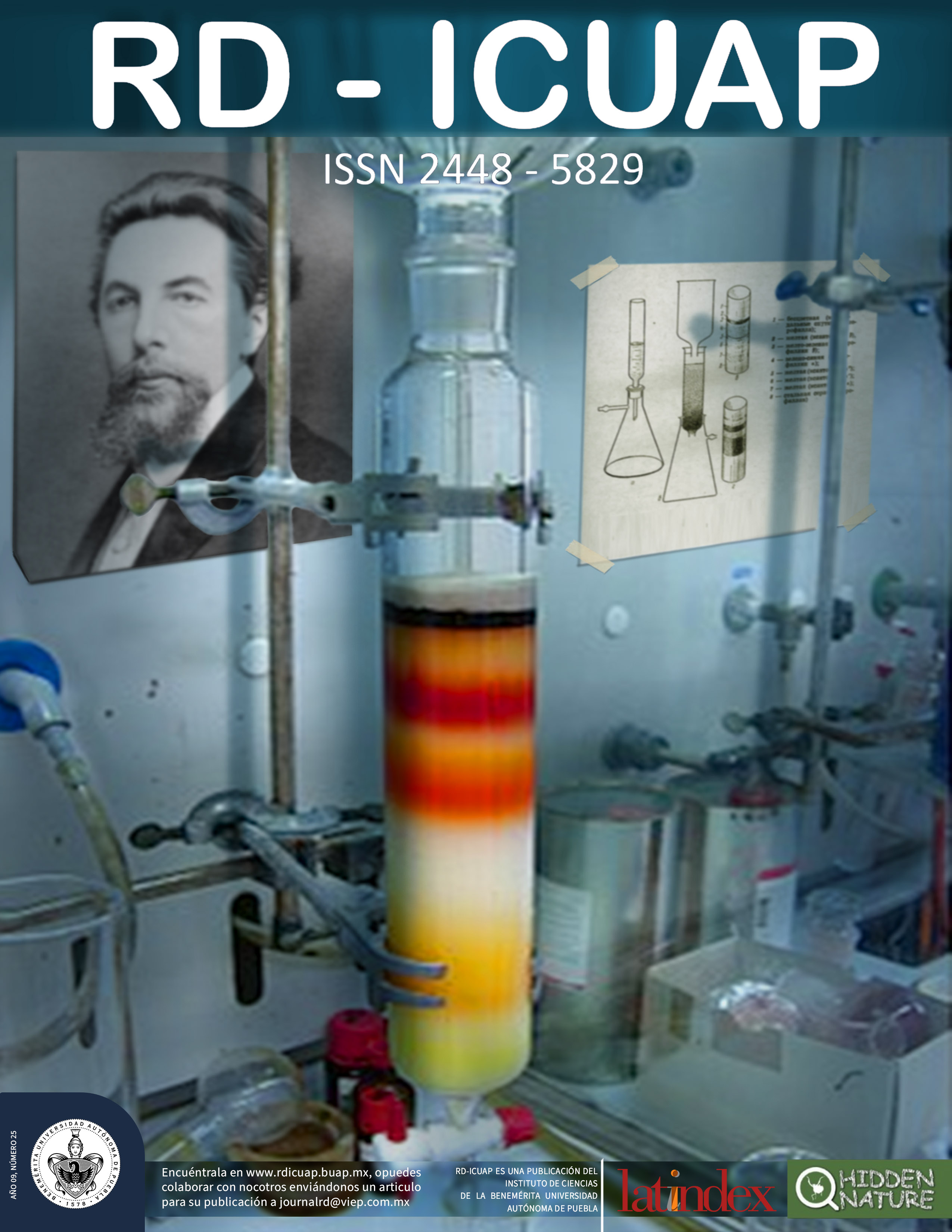

BIOTECNOLOGÍA A ALTAS TEMPERATURAS

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.32399/icuap.rdic.2448-5829.2023.25.1061Palabras clave:

ambiente extremo, termofilos, microorganismos, BiotecnologíaResumen

Los microorganismos representan una de las formas de vida más antiguas en el planeta, algunos de ellos pueden crecer en condiciones ambientales extremas que no permitirían el desarrollo de otros organismos, por ejemplo pueden ser resistentes a luz ultravioleta, a temperaturas cercanas al punto de ebullición o a bajo del punto de congelación del agua, pueden desarrollarse a alturas muy considerables o en la profundidad del océano, en presencia de compuestos nocivos, como metales pesados, gases tóxicos, pH muy ácido o básico e incluso a una alta concentración de sal, debido a esta versatilidad para poder crecer y reproducirse en ambientes extremos son formas de vida interesantes. El parque Nacional de Yellowstone es un ambiente hipertermal en el que se desarrollan diversos microorganismos, un ejemplo es la bacteria Thermus aquaticus, la cual fue aislada partir de muestras de este ambiente y su enzima ADN polimerasa es empleada en la Reacción en Cadena de la Polimerasa (PCR). En el presente artículo se mencionan ejemplos de microorganismos que son capaces de vivir a altas temperaturas y sus aplicaciones en el ámbito de la Biotecnología.

Citas

Cerqueda, D., Martínez, N., Falcón, L & Delaye, L. (2014). Metabolic analysis of Chlorobium chlorochromatii CaD3 reveals clues of the symbiosis in ‘Chlorochromatium aggregatum'. The ISME Journal, 8 (5), 991-998. http://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.207

Díaz, A., Roig, A., García. A & López, R. (2012). α-Enolase, a Multifunctional Protein: Its Role on Pathophysiological Situations. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology, 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/156795

Eisen, J. A., Nelson, K. E., Paulsen, I. T., Heidelberg, J. F., Wu, M., Dodson, R. J., ... & Fraser, C. M. (2002). The complete genome sequence of Chlorobium tepidum TLS, a photosynthetic, anaerobic, green-sulfur bacterium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(14), 9509-9514.

Fullerton, H & Moyer, C. (2016). Comparative Single-Cell Genomics of Chloroflexi from the Okinawa Trough Deep-Subsurface Biosphere. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 82 (10), 3000-3008. http://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00624-16

Gaisin, V., Kalashnikov, A., Grouzdev, D., Sukhacheva, M., Kuznetsov, B & Gorlenko, V. (2017). Chloroflexus islandicus sp. nov., a thermophilic filamentous anoxygenic phototrophic bacterium from a geyser. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 67, 1381-1386. http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001820

Garrity, G., Holt, J., Overmann, J., Pfennig, N., Gibson, J & Gorlenko, V. (2001). Phylum BXI. Chlorobi phy. nov. Bergey’s Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology (pp. 601-623). New York, USA: Springer.

Guiral, M., Prunetti, L., Aussignargues, C., Ciaccafava, A., Infossi, P., Ilbert, M., Lojou, E & Giudici-Orticoni, M-T. (2012). Chapter Four - The Hyperthermophilic Bacterium Aquifex aeolicus: From Respiratory Pathways to Extremely Resistant Enzymes and Biotechnological Applications. Advances in Microbial Physiology, 61, 125-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394423-8.00004-4

Hermoso, M. (2014). Morning Glory Pool. Yellowstone NP [imágen en-línea]. Wikimedia commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Morning_Glory_Pool_03.JPG

Herter, S. (2014). Chlororflexus aurantiacus [imágen en-línea]. Joint Genome Institut. https://genome.jgi.doe.gov/portal/chlau/chlau.home.html

Hiras, J., Wu, Y-W., Eichorst, S., Simmons, B & Singer, S. (2015). Refining the phylum Chlorobi by resolving the phylogeny and metabolic potential of the representative of a deeply branching, uncultivated lineage. The ISME Journal 10 (4), 833-845. http://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.158

Inskeep, W., Jay, Z., Tringe, S., Herrgard, M., Rusch, D & YNP Metagenome Project Steering Committee and Working Group Members. (2013). The YNP metagenome project: environmental parameters responsible for microbial distribution in the Yellowstone geothermal ecosystem. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4 (67), http://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00067

Ishino, S & Ishino, Y. (2014). DNA Polymerases as useful reagents for biotechnology – The history of developmental research in the field. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5:465, http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00465

Mehta, R., Singhal, P., Singh, H., Damle, D & Sharma, A. (2016). Insight into thermophiles and their wide-spectrum applications. 3 Biotech, 6 (81). http://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-016-0368-z

Monsalve, K., Roger, M., Gutierrez, C., Ilbert, M, Nitsche, S., Byrne, D., Marchi, V & Lojou, E. (2015). Hydrogen bioelectrooxidation on gold nanoparticle-based electrodes modified by Aquifex aeolicus hydrogenase: Application to hydrogen/ oxygen enzymatic biofuel cells. Bioelectrochemistry, 106, 47-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2015.04.010

Oliart, R., Manresa, A & Sánchez, M. (2016). Utilización de microorganismos de ambientes extremos y sus productos en el desarrollo biotecnológico. Ciencia UAT, volumen 11, 79-90. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-78582016000200079&lng=es&tlng=es.

Perry, J., Staley, J & Lory, S. (2002). Microbial Life. Massachusetts, USA: Sinauer Associates, Publishers.

Rainey, F & da Costa, M. (2015). Thermales ord. nov. Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118960608.obm00045

Ramírez, N., Serrano, J & Sandoval, H. (2006). Microorganismos extremófilos. Actinomicetos halófilos en México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Farmacéuticas, 37 (3), 56-71. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57937307

Ríos Vázquez, D. I. (2019). Identificación de microorganismos aislados de agua termal de Chignahuapan, Puebla. Tesis de Licenciatura en Biotecnología. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. https://repositorioinstitucional.buap.mx/handle/20.500.12371/4485

Sewell, H., Kaster, A & Spormann, A. (2017). Homoacetogenesis in Deep-Sea Chloroflexi, as Inferred by Single-Cell Genomics, Provides a Link to Reductive Dehalogenation in Terrestrial Dehalococcoidetes. American Society for Microbiology, 8 (6). http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02022-17

Sharma, N., Rai, A & Stal, N. (2014). Cyanobacteria an Economic Perspective. West Sussex, UK. Wiley Blackwell.

Shih, P., Ward, L & Fischer, W. (2017). Evolution of the 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle and recent transfer of anoxygenic photosynthesis into the Chloroflexi. National Academy of Sciences, 114(40), 10749-10754. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710798114

Sievert, S., Kiene, R & Schulz-Vogt, H. (2007). The Sulfur Cycle. Oceanography, 20 (2), 117-123. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2007.55

Sturchio, N., Bohlke, J & Markun, F. (1993). Radium isotope geochemistry of thermal waters, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, USA. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 57(6), 1203-1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(93)90057-4

Suárez, C., Ramírez, F., Monroy, O., Alazard, D & Fernández, L. (2004). La vida a altas temperaturas: adaptación de los microorganismos y aplicación industrial de sus enzimas. Ciencia, volumen 55 (1), 55-66. https://www.revistaciencia.amc.edu.mx/images/revista/55_1/lavida_altas_temperaturas.pdf

Sutcliffe, I. (2011). Cell envelope architecture in the Chloroflexi: a shifting frontline in a phylogenetic turf war. Environmental Microbiology, 13 (2), 279-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02339.x

Stetter, K.O. y Rachel, R. (2006). Aquifex pyrophilus [imágen en-línea]. Microbe Wiki. https://microbewiki.kenyon.edu/index.php/File:Aquifex-pt1.jpg

Tamazawa, S., Yamamoto, K., Takasaki, K., Mitani, Y., Hanada, S., Kamagata, Y & Tamaki, H. (2016). In Situ Gene Expression Responsible for Sulfide Oxidation and CO2 Fixation of an Uncultured Large Sausage-Shaped Aquificae Bacterium in a Sulfidic Hot Spring. Microbes and Environments, 31 (2), 194–198. http://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME16013

Theodorakopoulos, N., Bachar, D., Christen, R., Alain, K & Chapon, V. (2013). Exploration of Deinococcus-Thermus molecular diversity by novel group-specific PCR primers. Microbiology Open, 2 (5), 862-872. http://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.119

Treiman, A. (2002). Extremities: Biology and life in Yellowstone and implications for other worlds [imágen en-línea]. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/education/EPO/yellowstone2002/workshop/tbvspring2/index.html

Tortora, G., Funke, B & Case, C. (2007). Introducción a la Microbiología. Cd. de México, México: Médica Panamericana.

Van der Merwe, D. (2014). Freshwater cyanotoxins en Biomarkers in Toxicology (pp.539-548). USA: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-404630-6.00031-2

Vaughan, R., Heasler, H., Jaworowski, Lowenstern, J & Keszthelyi, L. (2014). Provisional Maps of Thermal Areas in Yellowstone National Park, based on Satellite Thermal Infrared Imaging and Field Observations. U.S. Geological Survey, Report 2014–5137, p.4. http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/sir20145137

Vijayakumar, S & Menakha, M. (2015). Pharmaceutical applications of cyanobacteria—A review. Journal of Acute Medicine 5 (1), 15-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacme.2015.02.004

Ward, L., Hemp, J., Shih, P., McGlynn, S & Fischer, W. (2018). Evolution of Phototrophy in the Chloroflexi Phylum Driven by Horizontal Gene Transfer. Frontiers in Microbiology, (9) 260, 1-16. http://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00260

White, W & Culver, David. (2012). Encyclopedia of Caves. New York, USA: Elsevier

Wiegel, J & Ljungdahl, L. (1985). The Importance Of Thermophilic Bacteria In Biotechnology. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, volume 3 (1), 39-108. https://doi.org/10.3109/07388558509150780

Zadvornyy, O., Boyd, E., Posewitz, M., Zorin, N & Peters, J. (2015). Biochemical and Structural Characterization of Enolase from Chloroflexus aurantiacus: Evidence for a Thermophilic Origin. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, (3) 74, 1-12 . http://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2015.00074

Descargas

Publicado

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

Definir aviso de derechos.

Los datos de este artículo, así como los detalles técnicos para la realización del experimento, se pueden compartir a solicitud directa con el autor de correspondencia.

Los datos personales facilitados por los autores a RD-ICUAP se usarán exclusivamente para los fines declarados por la misma, no estando disponibles para ningún otro propósito ni proporcionados a terceros.